A man brandishing a machete was responsible for my settling in Tenerife in 1960. He emerged from a plantation overlooking Puerto de la Cruz. As soon as I saw him, I knew I wanted the kind job that demanded I carry a cutlass!

At 18 and just out of school in Scotland, I had to choose my future. I’d failed to win entry to the BSc course in agriculture at Aberdeen University, so I decided to head for Argentina. My great-grandfather had gone there to build a railroad and never returned. But by the time I reached Santa Cruz de Tenerife, I was close to penniless. None of the cargo boats in the harbour were heading across the Atlantic. I was out of luck.

The quiet composure of the Tinerfeños and Santa Cruz’s drowsy timelessness captivated me. Tiers of little, coloured houses crept up the green hills behind the town. The air smelled of salt and warm vegetation. The perfect cone of Teide beckoned. Why not just stay and work? Here were people different from my own back in Scotland. I could learn a lot from them.

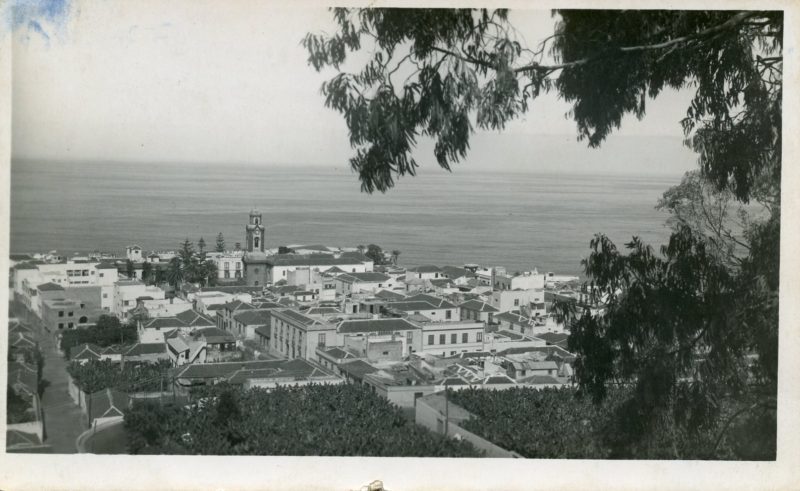

“Take the guagua to Puerto de la Cruz,” the harbour-master advised. “You’ll find work in construction.” But that sleepy little town proved silent and workless. What now? Night was approaching. I walked back up the hill to the main road. Puerto de la Cruz lay spread out beneath me, quiet, compact and dignified.

When suddenly I saw that daunting man with the machete step out of the plantation, I made up my mind. “I will find myself a job where that gleaming blade is the tool of choice.”

“In a banana plantation in Buenavista del Norte,” advised the plantation worker. “That’s where the work is!” Within 15 minutes, he’d hustled me into a guagua heading to that remote 15th-century village at the end of the narrow road on the tip of the island.

Throughout that journey, the driver, the conductor and the delighted locals plied me with questions. For most, it was their first encounter with an ‘extranjero’. ‘Forasteros’ and ‘peninsulares’ were odd enough, but a living, breathing ‘extranjero’ was real curiosity!

“Does your mamá know where you are?” “Do you shave yet?” “Why can’t you speak Spanish?” “Do they speak a Christian language where you come from?” “Why are you going to Buenavista?”

At the Pension Méndez on la Plaza de los Remedios, the driver presented me to Doña Lutgarda, the innkeeper. She scrutinized me from head to foot and then announced, “Forty-two pesetas a day. Room and meals. Your laundry is included.”

Snuggling around the Plaza de los Remedios, the stone church, the pension, the ‘venta’ — the general store — and the bar, together formed the beating heart of village life. In the 15th century, when Buenavista had been founded, streets were for people, mules and donkeys.

The village offered the warmth and comfort of timeless tradition, its simple, elegant buildings provided fitting harmony. Villagers were upright, hardworking, hospitable, friendly and above all, curious about the arrival of an ‘extranjero’.

First, Alcalde Don Paco García Martín, then his legal counsel Don Eduardo Champín Zamorano, and finally two nameless Civil Guards, checked me out with shrewd questions. They concluded that this 18-year-old Scotsman, kilt and all, was ‘buena gente’. I was welcome to stay if I adapted to village life.

During the year I spent there, everyone knew me simply as ‘El Extranjero’.

I explored the village, the rocky coast and the surrounding cliffs and barrancos. I learned Spanish and made friends. The Pension Méndez was my home. Doña Lutgarda and her girls, Pastora, Obdúlia, Angélica and Lula treated me like a distant relative from abroad.

They had never met anyone who couldn’t speak perfect Spanish, so they found my mistakes a constant source of fun. With their help, I learned the language quickly so I could fit in and find work.

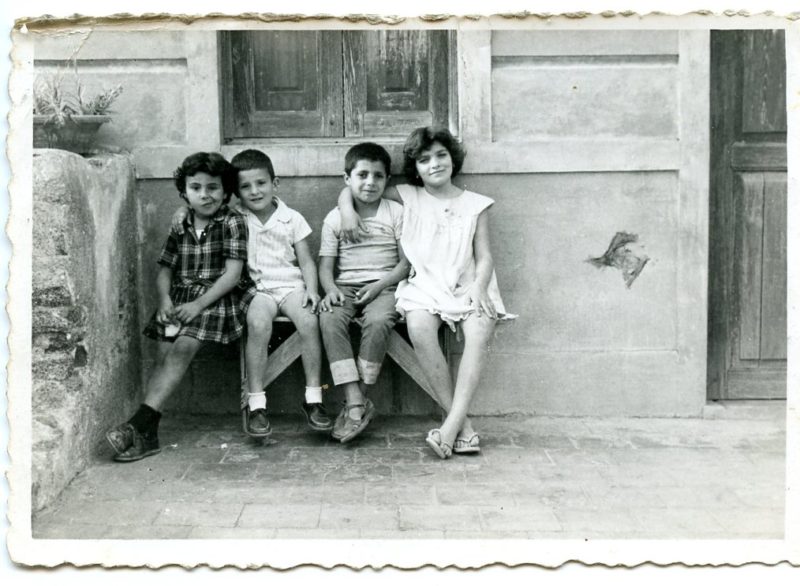

One day, I discovered Caya, Carmita, Toño and Mario, Doña Lutgarda’s grandchildren, in my room examining the contents of my rucksack. “What are you looking for?” I asked.

“Well,” said Caya – at 8 years old she was their leader — “you remember you told us your first tongue, the one you brought with you, was English? And that you wanted to get Spanish as your second tongue? Well, now that you have got your Spanish tongue, we’re trying to find your English one. We only want to see what it looks like!” Her tiny companions nodded soberly. “We want to see how different your first tongue is from the one you have now!”

Confusion is understandable when ‘lengua’ means both ‘language’ and ‘tongue’ at one and the same time!

Doña Lutgarda and her girls fed me well on gofio, lentejas, garbanzos, papas arrugadas and fresh fish. Within three weeks I could handle myself in Spanish. Now I was ready to find a job!

Doña Lutgarda Méndes Hernández and her large family, my co-workers and the villagers of Buenavista del Norte taught me a great deal. For their warm hospitality, for the gifts of their language and friendship, for sharing their culture and their ways, I salute the people of Tenerife with respect and gratitude.

Text and photos by Ronald Mackay

To discover more of Ronald’s amazing year-long adventure in Tenerife, take a look at his book here:

Fortunate Isle: A Memoir of Tenerife