Work was intensive at Alhambra, the banana export company where I worked in Buenavista del Norte in 1960. We might labour for 14 hours a day for three days and enjoy the rest of the week off. With so much free time, I was able to get to know the surrounding countryside. One of the most intriguing places was the ghost-village of Teno Bajo.

Two fishermen, Francisco-el-Diablo and his first-hand, would row me to El Callao de Márquez, a point half-way between Buenvista and La Punta de Teno. On the way, he delighted in scaring me. Standing up in the coble, each wielding an enormously long oar, Francisco and his partner would steer the coble as close as they could to las Rocas del Fraile.

At the moment the waves threatened to sweep us into the Fraile’s sharp fangs, the oarsmen would sweep away to seaward and laugh maniacally. They were consummate seamen. They knew the tides, and the rocks intimately. I was never truly afraid with them.

The first time I visited Teno Bajo they dropped me off on the large boulder near the shore. It was dangerous. I had to leap from the coble just as the wave rose 3 metres allowing me a fraction of a second to step off the gunwale onto the flat rock. There was an alternative route.

A seldom-used path from El Rincón snaked up the cliffs to Teno Alto, over the plateau, and then down the other side to Teno Bajo and on to La Punta de Teno. Villagers warned me against using it. The path was near-invisible and treacherous. Clouds might descend at any moment. Put a foot wrong and you would plunge a thousand metres into a ravine, torn to pieces on spiny cactus.

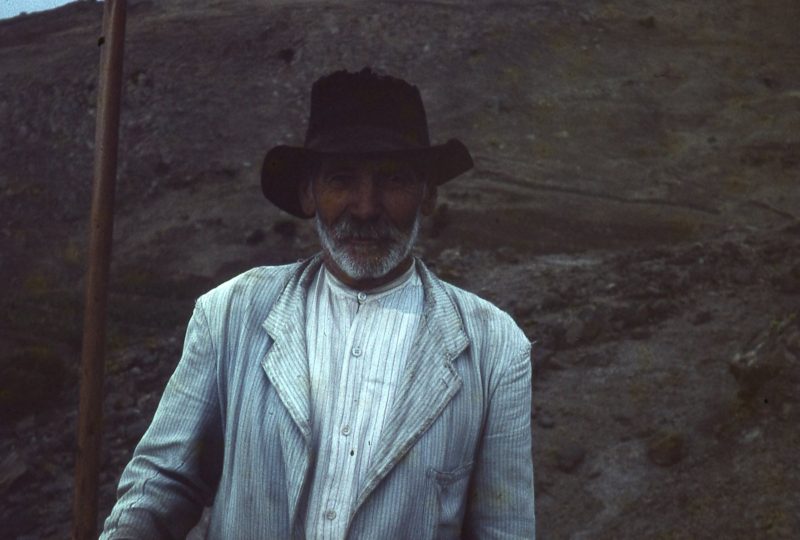

Teno Bajo was a collection of houses abandoned years before. Only Daniel and his wife remained as the mysterious custodians. They were accompanied by their son, his wife and over a hundred goats. Daniel and his family were always welcoming.

Daniel showed me the salt pans he’d dug on the shore and the bags of salt he collected after the seawater evaporated. He took the sacks to La Punta de Teno by donkey. Fishermen transported them on to Buenavista by row-boat.

Daniel showed me the first zurrón I’d ever seen. A zurrón is a crude leather bag made from the skin peeled off a kid-goat in one piece. The hair is scraped off, the skin cured and the holes made by removing the head and feet are sealed with wooden plugs. The resulting leather bag is used to mix gofio with honey to form sweet, moist nutritious balls that can sustain a working man throughout the entire day.

Why Daniel and his family chose to remain in the ghost-village of Teno Bajo was a mystery. It was whispered that he had opposed Franco and then sought refuge in isolation rather than be hanged from the notorious Puente de Hierro like so many.

From Teno Bajo, I could walk to the lighthouse at La Punta. Pepe the lighthouse-keeper was from La Peninsula. He, his wife and three children welcomed visitors. I visited often, usually by sea. Along with a few fishermen, we’d make the trip on a Sunday from Los Silos in a ‘falúa’, a boat powered by an inboard motor. To save time, we’d harvest fish for lunch, using a stick of dynamite.

One day, after we’d done our ‘fishing’, Pepe spotted the Civil Guard launch put out from Santa Catalina in La Gomera and head towards La Punta. The fishermen decided to escape back to Los Silos before the Beneméritos could catch them. Afraid that the presence of an ‘extranjero’ would complicate matters if they were caught, they dropped me off at El Callao de Márquez.

I immediately began running — first across the desert and then up the cliffs in the direction of Teno Alto. Suddenly the mist descended so thick that I was terrified to take more than one slow step at a time.

Fortunately, I met a shepherd and his granddaughter. Having lived up there all their lives, they refused to believe that I could be lost in such a familiar place. Finally, I made Abuelito understand my predicament. He had the 8-year-old child lead me confidently through the fog to the edge of the cliff and point out the near perpendicular path that led down to El Rincón.

I made it back safely. The fishermen too, made it safely back to Los Silos. But the Beneméritos poked around for days, trying to discover who had been dynamiting fish on a Sunday! Fortunately, Tinerfeños are loyal to their own – and by then, I counted as one of them!

Doña Lutgarda Méndes Hernández and her large family, my co-workers and the villagers of Buenavista del Norte taught me a great deal. For their warm hospitality, for the gifts of their language and friendship, for sharing their culture and their ways, I salute the people of Tenerife with respect and gratitude.

Text and photos by Ronald Mackay

To discover more of Ronald’s amazing year-long adventure in Tenerife, take a look at his book here:

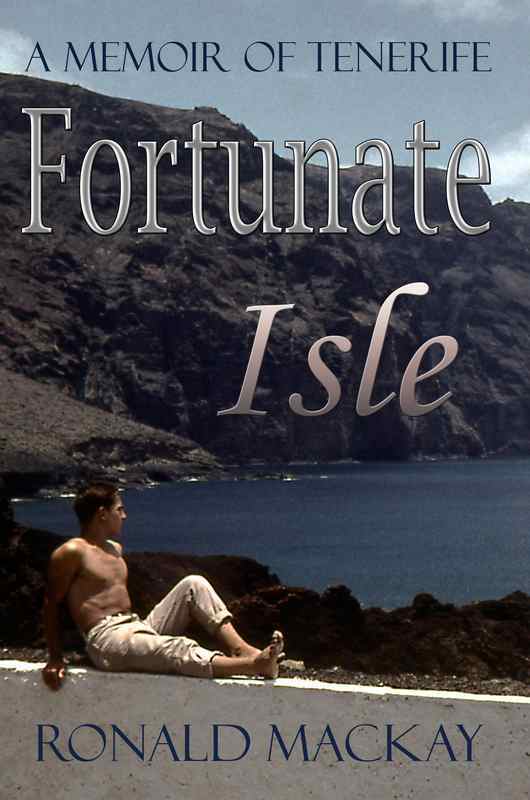

Fortunate Isle: A Memoir of Tenerife